Cantillon effect

The Cantillon Effect, named after Richard Cantillon, describes how money injection impacts recipients, allowing them to spend before price adjustments occur, leading to relative price changes. This process often benefits banks, financiers, and asset owners. The implications involve redistribution, distortions, and relevance to policies like quantitative easing (QE) and central bank asset purchases, which can result in asset price inflation. Some critiques include reliance on circulatory speed and open economies, with policy options like targeted transfers and inflation indexing being potential solutions[1][2].

Definition — What the Cantillon Effect is

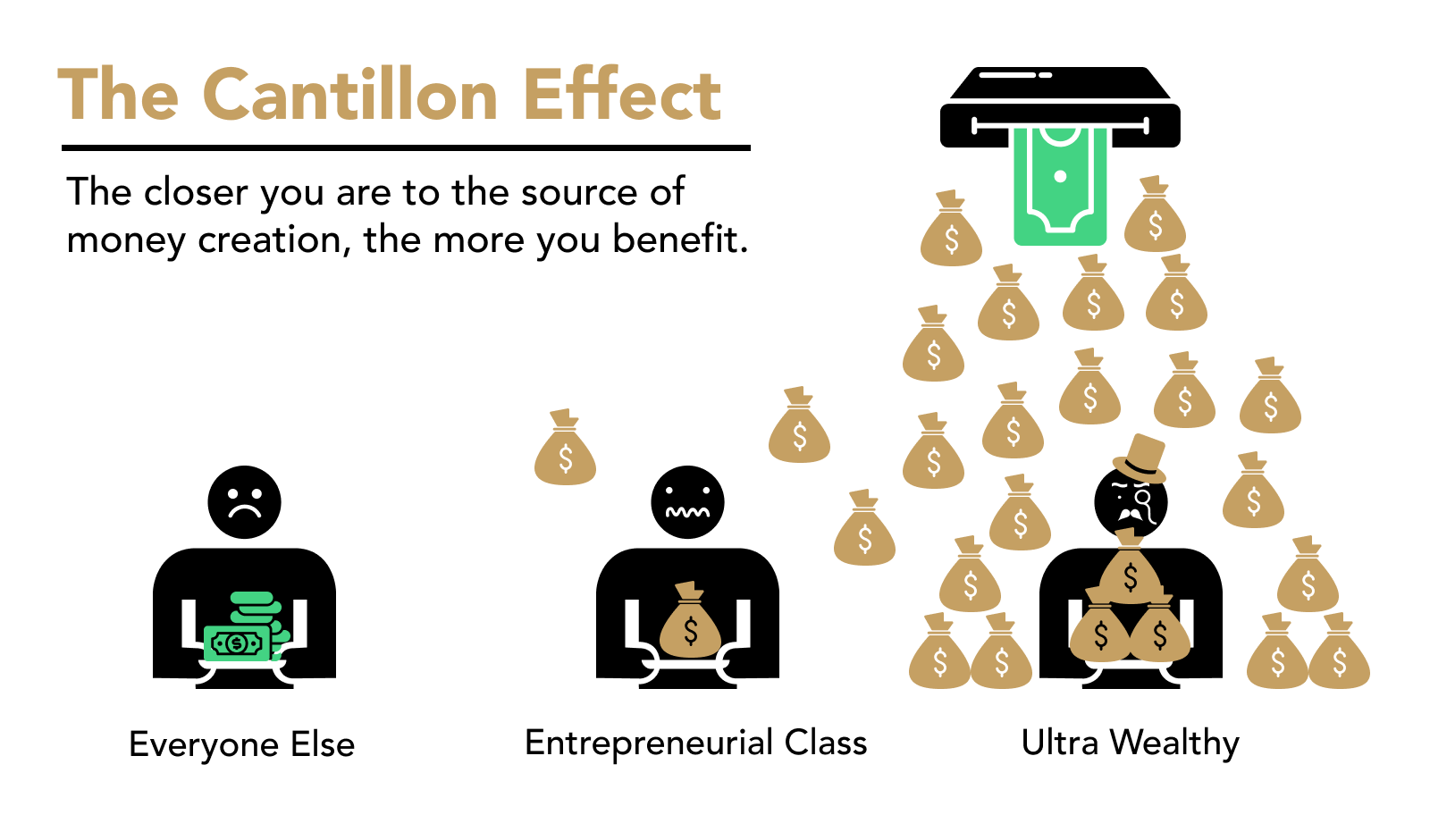

- The Cantillon Effect is the idea that changes in the money supply affect relative prices and wealth unevenly because the people or sectors who receive the new money first can spend or invest it before prices adjust for the increased money supply. [1:1][3]

Origin

- The concept was first described by Richard Cantillon in the early 18th century; he noted that where new money is injected into an economy matters for who benefits and which prices rise first. [2:1][4]

Mechanism (how it works)

- New money enters the economy at specific points (for example, banks, government contractors, or asset purchasers).

- Early recipients spend or invest the money at current prices, capturing value before general prices rise.

- As the new money circulates, demand increases and prices rise unevenly across goods, services, and assets — producing relative price changes rather than uniform inflation. [3:1][5]

Who tends to benefit and who tends to lose

- Beneficiaries: those close to the source of new money (banks, large investors, government suppliers, asset owners) can buy assets or inputs before price increases. [6][7]

- Losers: later recipients (wage‑earners, holders of cash or fixed incomes) face higher prices and effectively lose purchasing power as the adjusted prices propagate. [1:2][5:1]

Modern relevance and examples

- Central-bank actions such as quantitative easing (QE) are commonly discussed in Cantillon terms because asset purchases can inflate financial‑asset prices first, benefiting investors and banks more than wage‑earners. [3:2][8]

- Government deficit spending directed to particular industries or contractors can similarly redistribute purchasing power toward those sectors. [6:1][5:2]

Limitations and caveats

- The size and distributional impact depend on how quickly new money spreads, price stickiness, openness to imports (which can dampen domestic price rises), and the specific channels used to inject money. Measuring the effect precisely in real economies is difficult. [3:3][2:2]

Why it matters

- The Cantillon Effect shows that inflation is not “neutral”: monetary expansions can reallocate wealth and resources, so monetary policy has distributional and structural consequences beyond aggregate price levels. [1:3][7:1]

- Biflation: Definition, Causes, and Example - Investopedia ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

- Money, Inflation, and Business Cycles: The Cantillon Effect and the... ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

- Cantillon Effects: Why Inflation Helps Some and... | Mises Institute ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

- Richard Cantillon - Wikipedia ↩︎

- Cantillon Effect | River ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

- The Cantillion Effect - Adam Smith Institute ↩︎ ↩︎

- The Cantillon Effect: Because of Inflation, We’re Financing the Financiers ↩︎ ↩︎

- The Cantillon Effect: Why Early Access to Money Matters ↩︎